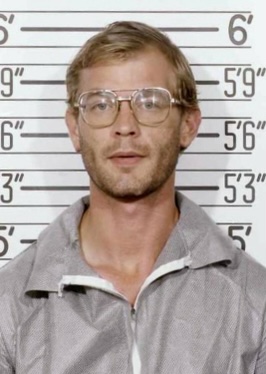

In 1991, police in Milwaukee, Wisconsin apprehended one of the most infamous serial killers in American history. In July of that year, authorities were alerted to the apartment of Jeffrey Lionel Dahmer, where they encountered a depth of human depravity that few have ever witnessed. It was soon revealed that Dahmer was a prolific killer, having murdered 17 victims since 1978. Over the years, morbid curiosity has turned Dahmer into somewhat of a poster child for true crime enthusiasts. The extent of Dahmer’s unimaginable crimes, which I do not wish to rehash here, has been extensively researched, appearing in a bevy of media outlets such as books, podcasts, true crime documentaries, and movies. But few have bothered to highlight perhaps the most fascinating chapter in this harrowing story.

After his capture, Dahmer expressed immediate culpability and remorse for his heinous acts. His 1992 statement to the court reads,

Your Honor, . . . I know my time in prison will be terrible, but I deserve whatever I get because of what I have done. Thank you, Your Honor. I am prepared for your sentence, which I know will be the maximum. I ask for no consideration . . .

It’s hard for me to believe that a human being could have done what I’ve done, but I know I did.

Quoted in Ratcliffe, Dark Journey, Deep Grace pp. 23, 37.

At the conclusion of his trial, Jeffrey famously said,

Your Honor, it is over now. This has never been a case of trying to get free. I didn’t ever want freedom. Frankly, I wanted death for myself . . . I believe I was sick . . . I know how much harm I have caused . . . I feel so bad for what I did to those poor families, and I understand their rightful hate . . . I am so very sorry.

Quoted in Ratcliffe, Dark Journey, Deep Grace p. 53.

In 1994, after Dahmer was convicted and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences, Wisconsin pastor Roy Ratcliff received a bizarre request from an Oklahoma prison ministry. An inmate in Wisconsin had requested that a Bible be mailed to him, completed a correspondence study course, and asked to be baptized. That inmate, shockingly, was none other than Jeffery Dahmer. In his memoir, Dark Journey, Deep Grace: Jeffrey Dahmer’s Story of Faith, Ratcliffe admits he was initially skeptical, suspicious that he was the subject of a grotesque prank. However, upon contacting the prison chaplain, Ratcliffe confirmed that the request was real: Jeffrey Dahmer, serial killer, had professed faith and requested to be baptized in the name of Jesus.

Jeffrey Dahmer was baptized on May 10, 1994. In the months leading up to Dahmer’s death later that year, Roy Ratcliff’s belief in the sincerity of Jeffrey’s profession of faith only grew stronger. Weekly meetings became a genuine friendship as Ratcliff and Dahmer addressed Jeffrey’s many questions about Christian doctrine and practice. Dahmer had grown up in a religious family – his mother and father were members of the Church of Christ – and Jeffrey was quite familiar with Christian worship. Dahmer’s main concern, however, was the practicality of worshiping while incarcerated. For example, the prison only offered Communion once a month, but Jeffrey was convicted that he needed to take it every Sunday (as is the practice of the Church of Christ denomination). To make matters worse, wine (or even grape juice) was not permitted in prison, so grape Kool-Aid was used in its place. Dahmer had to be reassured that God knew his situation and would be pleased with Jeffrey’s desire to worship him in the ways he was capable of. Perhaps this speaks to a lingering insecurity in Jeffrey, as if he found some reassurance of his salvation in adhering as strictly as possible to doctrine and practices. Perhaps it was simply because he found new life in Christ and wanted to live it for all it was worth. Likely, it was a combination of both. Jeffrey acknowledged that both his sins and the forgiveness found in Jesus were beyond the scope of what is comprehensible.

In November of 1994, just a few short months after he was baptized, Jeffrey Dahmer was murdered by a fellow prison inmate. The reaction among the public was immediate. Sentiments ranged from joy that Dahmer had been killed – a sentence that he certainly would have received if Wisconsin were a death penalty state – to outrage that Dahmer had somehow “escaped” the torment he deserved as recompense for the suffering he had caused. On the other side of the spectrum were Dahmer’s parents, Lionel and Joyce, and his new friend Roy Ratcliff. They grieved, both for the loss of their son and friend, but also for the chaos and destruction that Jeffrey had wrought on his own life and the lives of his victims. Couched in grief, however, was rejoicing. Jeffrey’s eternity was secure. He was with Jesus.

People tend to repulse at Jeffrey’s story. What kind of God, they argue, would let such a man off the hook for what he has done? “If Jeffrey Dahmer is in heaven,” some might say, “then I want no part of heaven.” Others may say highlighting Dahmer’s faith and transformation is disrespectful to the memory of his victims; that our posture toward Dahmer should be vitriol and hatred, rather than seeking to humanize him. Others greet Dahmer’s story with skepticism: this was a deranged psychopath who was trying to keep the spotlight on himself, or desperately bargain with whatever divine powers he could find to feel at peace with what he had done.

Skepticism and vitriol toward the salvation of another, however, are unbecoming of grace. It is understandable that one might think a grave injustice has been done if Jeffrey Dahmer is indeed in heaven. However, we must not let our idea of justice detract from what grace is. If grace were contingent on justice, then no one would be saved from their sin. However, if God absolved all sin without consequence, then God would not be truly just. This is the beauty and significance of the cross, wherein God’s grace provided what his justice required. The death of Jesus Christ on the cross was sufficient for all sin. To suggest that particular sins, however heinous, are unforgivable, is to cheapen the power of the cross.

In response to the anger that Jeffrey Dahmer’s salvation stirs in people of faith, God’s question to Jonah comes to mind: “Is it good for you to be angry?” Jeffrey’s conversion is not unlike Paul’s. Paul was notorious for his brutal persecution of the church. He was responsible for the death of scores of innocent people. But Paul’s assurance of his salvation was not rooted in his past, but in the redemptive power of Jesus’ death and resurrection. He famously wrote,

“The saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost.”

1 Timothy 1:15

I don’t know if Jeffrey Dahmer is in heaven. We can’t know for certain if his yearning for Jesus was sincere. But I choose to believe that human depravity will never overshadow Jesus’ eagerness and ability to meet us in our brokenness. If he can reach down into death and bring new life to a decaying body, he can certainly bring resurrection to even the deadest of souls. Jeffrey Dahmer is no exception. I also trust the testimony of a brave, merciful, compassionate pastor who had the audacity to believe that heaven is big enough for Jeffrey Dahmer, and who proudly called him a brother in Christ.

I don’t want to stir division, and I don’t want to diminish Dahmer’s crimes. I am not arguing that he was a good man, or that he deserved grace. But the hard truth is that I don’t deserve grace either, and neither do you. Therefore, there is no sense in doling out judgment on behalf of God for sins that we deem to be “worse”. Why celebrate a grace that we don’t deserve, while also celebrating the judgment of another? Jeffrey’s story is a testament to the sheer incomprehensibility of grace, an invitation to marvel at “how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ” (Eph. 3:18). As the father beckoned the malcontent brother to join the celebration of the prodigal’s return, Jeffrey’s story confronts us with the same pressing question: Is our view of grace too small?

Excerpts in this post are from Dark Journey Deep Grace by Roy Ratcliffe and Lindy Adams. Cover image via Wikipedia.org.

Leave a comment